Methane, a potent greenhouse gas, is being released from landfills It is oil and gas operations around the world in far greater quantities than governments imagined, recent aerial and satellite surveys show. This is a problem for the climate and also for human health. This is also why the US government has been stricter regulations about methane leaks and unnecessary ventilation, most recently from oil and gas wells on public lands.

The good news is that many of these leaks can be fixed – if they are caught quickly.

Riley Durenresearch scientist at the University of Arizona and former NASA engineer and scientist, leads Carbon Mapper, a nonprofit organization that is planning a constellation of methane monitoring satellites. Its first satellite, a partnership with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Earth imaging company Planet Labs, will launch in 2024.

Duren explained how new satellites are changing the ability of companies and governments to find and stop methane leaks and avoid wasting a valuable product.

Why are methane emissions so concerning?

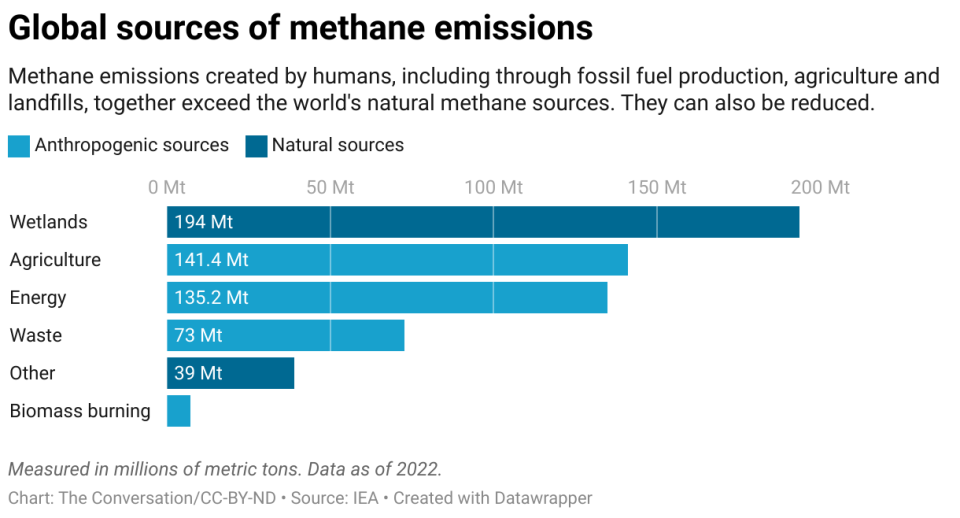

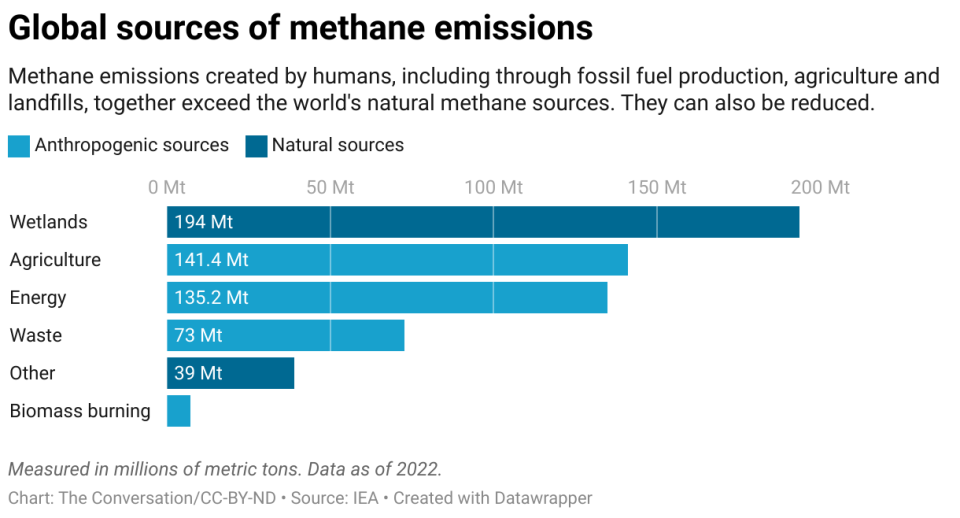

Methane is the second most common global warming pollutant after carbon dioxide. It doesn’t stay in the atmosphere for that long – only about a decade compared to centuries for carbon dioxide – but it has an outsized impact.

Methane ability to heat the planet it is almost 30 times greater than carbon dioxide in 100 years and more than 80 times in 20 years. You can think of methane as a very effective blanket that traps heat in the atmosphere, warming the planet.

What concerns many communities is that methane is also a health problem. It is a precursor to ozone, which can worsen asthma, bronchitis It is other lung problems. And in some cases, methane emissions are accompanied by other harmful pollutantssuch as benzene, a carcinogen.

In many oil and gas fields, less than 80% of the gas coming out of the ground from a well is methane – the rest can be dangerous air pollutants that you wouldn’t want near your home or school. However, until recently, there was much little direct monitoring to find leaks and stop them.

Why are satellites needed to detect methane leaks?

In its natural form, methane is invisible and odorless. You probably wouldn’t know there was a huge methane cloud next door if you didn’t have special instruments to detect it.

Companies have traditionally accounted for methane emissions using a 19th-century method called an inventory. Inventories calculate emissions based on reported production from oil and gas wells or the amount of trash that goes to a landfill, where organic waste generates methane as it decomposes. There is a lot of room for error in this assumption-based accounting; for example, it does not take into account unknown leaks or persistent ventilation.

Until recently, the state of the art in leak detection in oil and gas operations involved a technician visiting a well every 90 days or so with a portable infrared camera or gas analyzer. But a large leak could release a huge amount of gas over a period of several days and weeks or may occur in places not easily accessible, meaning that many of these so-called super emitters go unnoticed.

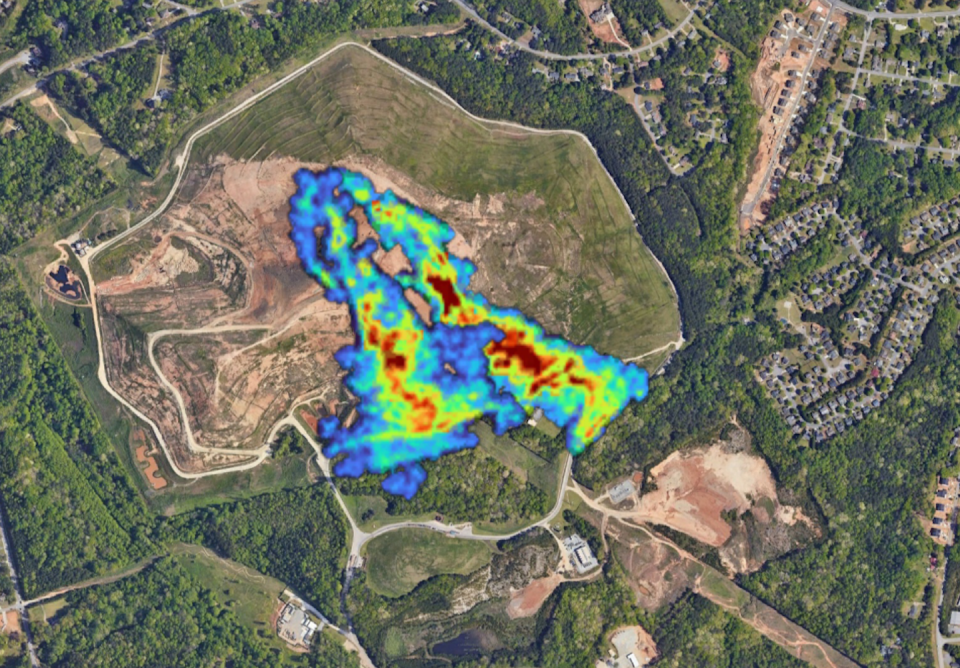

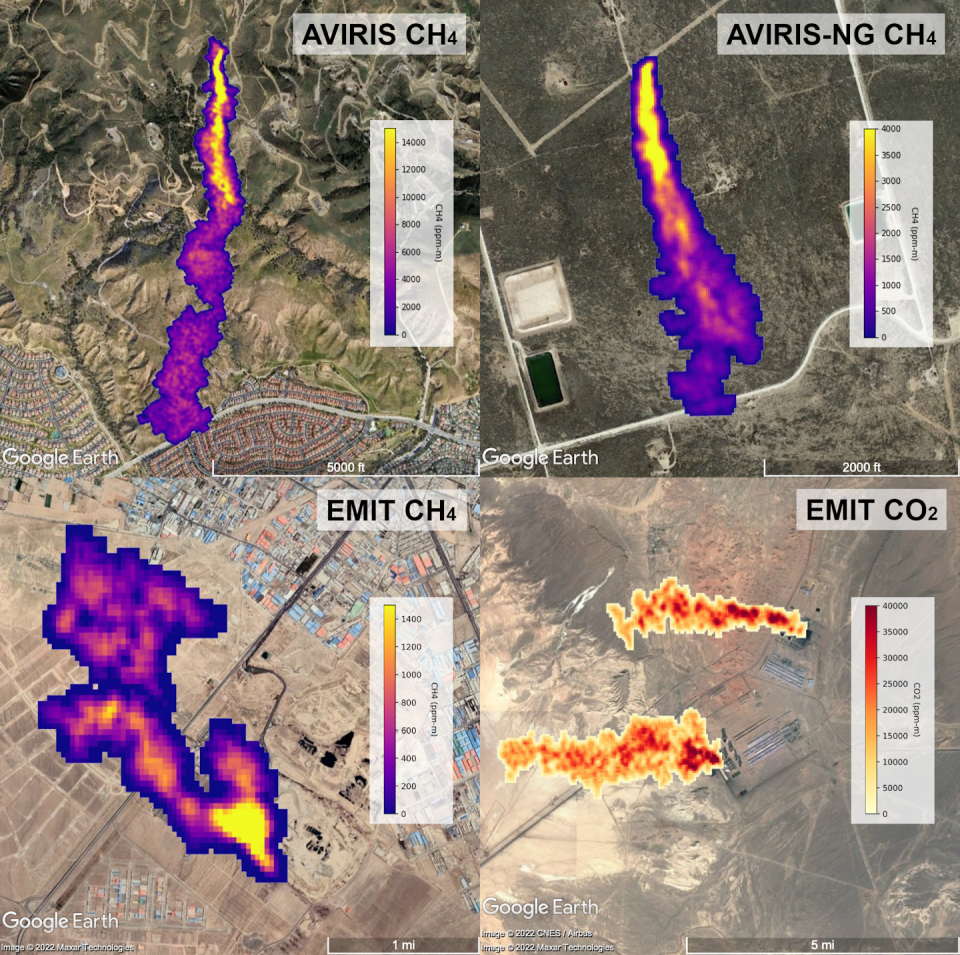

Remote sensing satellites and planes, on the other hand, can quickly survey large areas on a routine basis. Some of the newer satellites, including those we are launching through the Carbon Mapper Coalition, can enlarge individual websites in high resolutionso we can identify super methane emitters in the well, compressor station or specific section of a landfill.

You can see an example of the power of remote sensing in our recent article in Science magazine. We search 20% of open landfills in the USA with airplanes and found that emissions were, on average, 40% higher than emissions reported to the federal government using assumption-based accounting.

If scientists can monitor regions frequently and consistently from satellites, then they can flag superemitter activity and notify the operator quickly so that the operator can find the problem while it is still happening and fix any leaks.

How do satellites detect methane in space?

Most satellites capable of detecting methane use some form of spectroscopy.

A typical camera sees the world in three colors – red, green and blue. The imaging spectrometers we use were developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and see the world in nearly 500 colors, including wavelengths beyond the visible to infrared spectrum, which is essential for greenhouse gas detection and measurement.

Greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide absorb heat at infrared wavelengths – each with unique fingerprints. Our technology analyzes sunlight reflected from the Earth’s surface to detect the infrared fingerprints of methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

These signatures are distinct from all other gases, so we can image methane and carbon dioxide plumes to determine the origins of individual super-emitters. Since we use spectroscopy to measure the amount of gas in a given plume, we can calculate an emission rate using wind speed data.

What can the new satellites Carbon Mapper plans to launch do that others haven’t yet?

Each satellite has different and often complementary capabilities. MetanoSat, which the Environmental Defense Fund just launched in March 2024, is like a wide-angle lens that will produce a very accurate and complete picture of methane emissions across large landscapes. Our Carbon Mapper Coalition satellites it will complement MethaneSAT by acting like a collection of telephoto lenses – we will be able to zoom in to locate individual methane emitters, like zooming in on a bird nesting in a tree.

Working with our partners at Planet Labs and NASA, we plan to launch the first Carbon Mapper Coalition satellite in 2024, with the goal of expanding the constellation in the coming years to ultimately provide daily methane monitoring in high-priority regions in Worldwide. For example, it is estimated that around 90% of methane emissions from the production and use of fossil fuels are come from just 10% of the Earth’s surface. Therefore, we plan to focus Carbon Mapper Coalition satellites on oil, gas, and coal production basins; large urban areas with refineries, wastewater treatment plants and landfills; and main agricultural regions.

How will your monitoring data be used?

We expect, based on our aircraft data sharing experience with facility operators and regulators, that much of our future satellite data will be used to guide leak detection and repair efforts.

Many oil and gas companies, landfill operators, and some large farms with methane digesters are motivated to find leaks because the methane in these cases is valuable and can be captured and put to use. Therefore, in addition to climate and health impacts, methane leaks are equivalent to the release of profits into the atmosphere.

With routine satellite monitoring, we can quickly notify facility owners and operators so they can diagnose and correct any problems, and we can continue monitoring sites to ensure leaks remain fixed.

Our data can also help alert nearby communities to risks, educate the public, and guide enforcement efforts in cases where companies do not voluntarily fix their leaks. By measuring trends in high methane emission events over time and across basins, we can also contribute to assessments of whether policies are having the intended effect.

This article was republished from The conversation, an independent, nonprofit news organization that brings you trusted facts and analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Riley Duren, University of Arizona

See more information:

Riley Duren is CEO of the nonprofit Carbon Mapper. Carbon Mapper receives funding from several philanthropic organizations, as well as grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.