Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

Performing administrative tasks in ancient Egypt may not seem physically demanding, but new research has revealed that being a scribe left a mark on the skeletons of the men who held these privileged positions.

Scribes were high-status men with the ability to write and were part of the 1% of the literate population, according to the authors of a new study published Thursday in the journal. Scientific Reports.

But the tasks performed by scribes were repetitive. Today, office workers look for chairs with ergonomic support to spend long hours sitting at a desk. Egyptian men assumed one of three positions that became an occupational hazard, the study authors found.

Researchers analyzed the remains of 69 men buried in a necropolis in Abusir, Egypt, between 2700 BC and 2180 BC. Thirty of the men were scribes, as marked on their tombs, and their skeletons showed more degenerative joint changes in specific areas of their bodies than the other remains.

The discoveries open a new window into what life was like for scribes in ancient Egypt during the third millennium BC.

Becoming a scribe

The remains analyzed in the study belonged to men who lived in the heyday of ancient Egypt during the Old Kingdom, or the era of the pyramid builders, said study co-author Veronika Dulíková, an Egyptologist at the Czech Institute of Egyptology at Charles University in Prague.

Records from that time indicate to researchers that children from elite families were educated at the royal court.

“From a very early age, as teenagers, they signed up to fill entry-level positions in various administrative positions to get the training they needed to advance their careers,” Dulíková said in an email. “They then rose through the ranks of the positions they held.”

At the time, literacy was in its infancy, she said. “There was no need for a predominantly agricultural population to know how to read and write.”

Scribes in ancient Egypt held positions not unlike government positions in modern society.

“These people belonged to the elite of the time and formed the backbone of the state administration,” Dulíková said. “Literate people worked in important government departments such as the treasury (today the Ministry of Finance), the granary (today the Ministry of Agriculture), the department of royal documents, etc. cults and in real pyramid complexes.”

The role of scribes was crucial in ancient Egyptian society, but the records they left behind were even more valuable to researchers.

“The ancient Egyptians kept careful records of everything, which they then stored in archives,” Dulíková said. “When we find a paper file like this today, it is literally a treasure. From such records we can learn a lot about the functioning of the temple complexes, the services rendered by the officials in the temples, the form of their salaries, what furniture or utensils were stored in the temple storerooms, etc.”

The Egyptians were so detailed that they included written records directly in the tombs to identify the positions, careers, and ranks of the men buried there, which helped researchers identify administrative scribes.

Skeletal clues

The study’s lead author, Petra Brukner Havelková, an anthropologist at the National Museum in Prague, has specialized in identifying activity-induced skeletal markers for nearly 20 years.

When Havelková looked at the remains discovered at Abusir and identified examples of strain on the cervical spine, she realized there could be a link between skeletal degeneration and men’s occupations.

The first skeletons of people from the Old Kingdom were discovered in 1976 in Abusir, but it took decades to unearth more.

After failing to find any research on degenerative joint and bone diseases in ancient scribes, Havelková teamed up with Dulíková and other colleagues to conduct a study of her own. They began marking changes in the scribes’ skeletons in 2009, but it took another decade to find enough remains for a comprehensive study.

During the analysis, researchers discovered that scribes had a higher incidence of osteoarthritis, or a disease in which joint tissues break down over time.

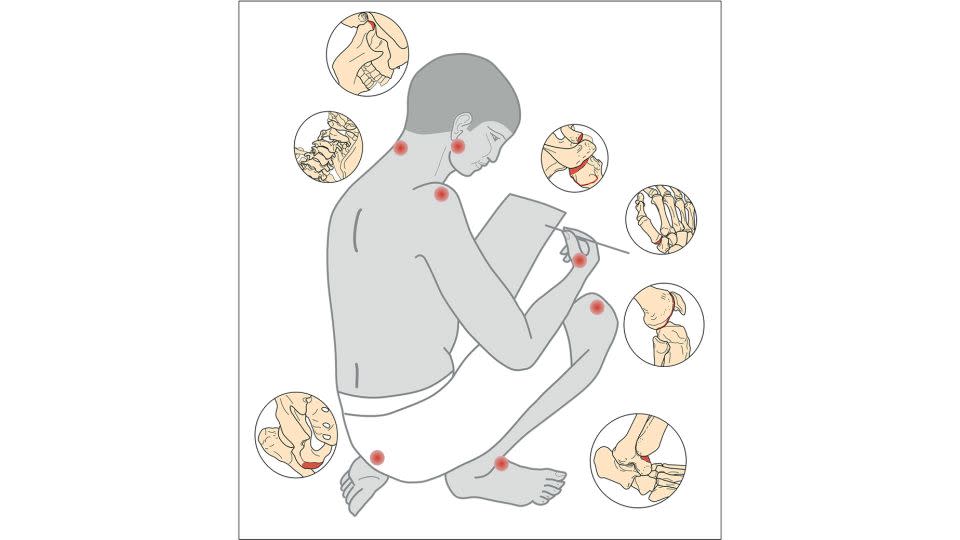

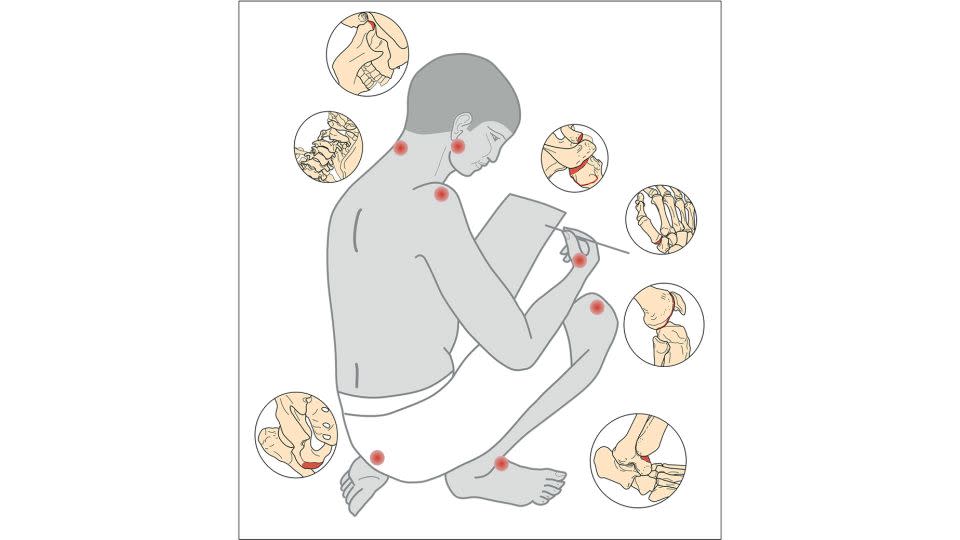

These changes were observed in the joints that connect the jaw to the skull, in the right collarbone, in the upper part of the right arm bone connected to the shoulder, in the lower part of the thigh, in the bones of the right thumb and throughout the spine.

There were also visible changes, such as a flattened part of the bone on the lower right ankle and indentations on both kneecaps.

Most of the skeletal changes can be attributed to the positions that scribes assumed while carrying out their work, which was recorded in tomb wall decorations and statues. Scribes stood, kneeled, or sat cross-legged for long periods of time while writing.

If they sat cross-legged, their stretched skirts served as a table, according to the researchers. In this position, they probably sat for hours, with their head tilted forward, their arms unsupported, and their spine flexed.

But skeletal changes in the knees, hips, and ankles also point to a crouched or crouched position favored by many scribes. It is likely that the scribes were sitting with their left legs kneeling or crossed, while their right legs were bent with the knees pointing upwards.

A surprise in the jaw joint

Scribes also chewed the ends of the reed stems they used for writing instruments to create brush-like heads that they spent hours holding in a pinch-like position.

Chewing explains why their jaws were overloaded, while long hours of writing likely caused the skeletal changes seen in their right thumbs, the researchers said.

The researchers were less surprised to find changes in the lower limbs because sitting cross-legged and kneeling were common among the entire population at the time, but they did not expect the changes in the jaw.

“The biggest surprise was the extreme overload of the scribes’ jaw joints,” Havelková said in an email. “This was something we hadn’t even imagined initially, focusing mainly on the rest of the skeleton outside the skull.”

Sonia Zakrzewski, professor of bioarchaeology and bioanthropology at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, called the research “groundbreaking.” She was not involved in the study.

“He synthesizes both the Egyptological record (including the pictorial and sculptural evidence) with the bioarchaeological evidence of activity-related skeletal changes to argue that the changes in muscle attachment sites and the location of the arthritic changes suggest that the affected individuals were scribes,” Zakrzewski said in an email.

“One of the main questions we have in bioarchaeology is that we don’t know exactly how much, how long and/or how often activities must be performed for skeletal change to occur – but we do know that our bodies remodel in response to such strains. This integration of other aspects of archeology with the skeletal record is necessary in bioarchaeology and this study is a good example of this type of approach. “

Now, researchers want to collaborate with other groups to study and analyze scribes and other individuals in different ancient Egyptian cemeteries, such as the cemetery in Saqqara.

“Together with our ‘neighbors’ in Saqqara, we share a common goal, which is to learn as much as possible about the life and death of the people who lived during the time of the pyramid builders,” said Havelková.

For more news and newsletters from CNN, create an account at CNN.com