Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

Four years ago, the unexpected discovery in the clouds of Venus of a gas that on Earth means life – phosphine – faced controversygain reprimands in subsequent observations that did not match his findings.

Now, the same team behind that discovery has returned with more observations, presented for the first time on July 17 at a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society in Hull, England. Eventually, they will form the basis of one or more scientific studies, and that work has already begun.

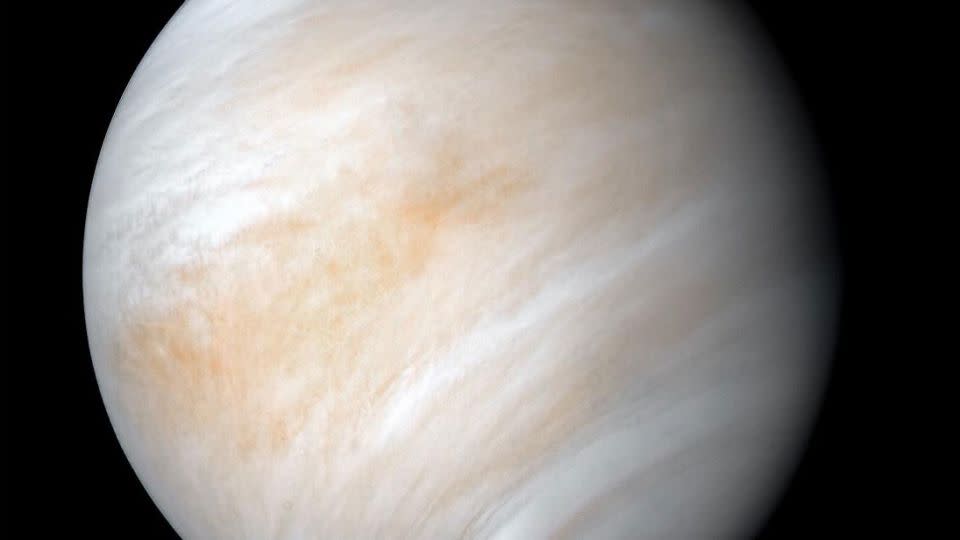

The data, researchers say, contains even stronger evidence that phosphine is present in the clouds of Venus, our closest planetary neighbor. Sometimes called Earth evil twinThe planet is similar in size to ours, but features surface temperatures that can melt lead and clouds made of corrosive sulfuric acid.

The work benefited from a new receiver installed on one of the instruments used for the observations, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii, giving the team more confidence in their discoveries. “There’s also a lot more data in itself,” said Dave Clements, reader in astrophysics at Imperial College London.

“We ran three observation campaigns, and in just one run we got 140 times more data than in the original detection,” he said. “And what we have obtained so far indicates that we once again have detections of phosphine.”

A separate team, of which Clements is also a member, presented evidence of another gas, ammonia.

“This is arguably more significant than the discovery of phosphine,” he added. “We are a long way from saying this, but if there is life on Venus producing phosphine, we have no idea why it is producing it. However, if there is life on Venus producing ammonia, we have an idea why it might want to breathe ammonia.”

Sign of life?

On Earth, phosphine is a toxic, foul-smelling gas produced by the decomposition of organic matter or bacteria, while ammonia is a gas with a pungent smell that occurs naturally in the environment and is also mainly produced by bacteria at the end of the decomposition process. of plant and animal residues.

“Phosphine was discovered in Saturn’s atmosphere, but this is not unexpected because Saturn is a gas giant,” Clements said. “There is a huge amount of hydrogen in its atmosphere, so any hydrogen-based compounds, like phosphine or ammonia, are the ones that dominate there.”

However, rocky planets like Earth, Venus and Mars have atmospheres in which oxygen dominates the chemistry, because they did not have enough mass to hold the hydrogen they had when they originally formed, and that hydrogen escaped.

Finding these gases on Venus is therefore unexpected. “By all normal expectations, they shouldn’t be there,” Clements said. “Phosphine and ammonia have been suggested as biomarkers, including on exoplanets. So finding them in the atmosphere of Venus is also interesting in that sense. When we published the phosphine discoveries in 2020, it was understandably a surprise.”

Subsequent studies disputed the results, suggesting that phosphine was actually common sulfur dioxide. Data from instruments other than those used by Clements’ team – such as the Venus Express spacecraftO NASA Infrared Telescope Facility and the now extinct SOFIA airborne observatory – also failed to replicate the phosphine discoveries.

But Clements said his new data, coming from Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, excludes that sulfur dioxide could be a contaminant and that the lack of phosphine in other observations is due to age. “It turns out that all of our observations that detected phosphine were made as Venus’ atmosphere moved from night to day,” he said, “and all of our observations that didn’t find phosphine were made as the atmosphere moved from day to day.” for the night. .”

During the day, ultraviolet light from the Sun can break down molecules in Venus’s upper atmosphere. “All the phosphine is burned and that’s why we don’t see it,” Clements said, adding that the only exception was the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, which made observations at night. But further analysis of this data by Clements’ team revealed faint traces of the molecule, reinforcing the theory.

Clements also pointed to to look for from a group led by Rakesh Mogul, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Mogul reanalyzed old NASA data Large Pioneer Venus Probewhich entered the planet’s atmosphere in 1978.

“It showed phosphine within the clouds of Venus at around the part-per-million level, which is exactly what we have largely detected,” Clements said. “So it’s starting to come together, but we still don’t know what’s producing it.”

Using data from the Pioneer Venus Large Probe, the team led by Mogul in 2021 published a “compelling case for phosphine deep in (Venus’) cloud layer,” Mogul confirmed in an email. “To date, our analyzes remain unchallenged in the literature,” said Mogul, who was not involved in the Clements team’s research. “This is in stark contrast to telescopic observations, which remain controversial.”

Respiratory microbes?

Ammonia on Venus would be an even more surprising discovery. Presented at lectures in Hull by Jane Greaves, professor of astronomy at Cardiff University in the UK, the findings will form the basis of a separate scientific paper, using data from the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia.

Venus’s clouds are made of droplets, Clements said, but they are not water droplets. There is water in them, but also so much dissolved sulfur dioxide that they turn into extremely concentrated sulfuric acid – a highly corrosive substance that can be deadly to humans with severe exposure. “It’s so concentrated that, as far as we know, it wouldn’t be compatible with any life we know on Earth, including extremophile bacteria, which like very acidic environments,” he said, referring to organisms that are able to survive in extreme environmental conditions.

However, the ammonia inside these acid droplets can act as a buffer for the acidity and reduce it to a low enough level that some known terrestrial bacteria can survive in it, Clements added.

“The interesting thing behind this would be if there was some kind of microbial life producing ammonia, because that would be a cool way of regulating its own environment,” Greaves said at the Royal Astronomical Society lectures. “This would make your environment much less acidic and much easier to survive in, to the point where it would be as acidic as some of the most extreme places on Earth – so not completely crazy.”

The role of ammonia, in other words, is easier to explain than phosphine. “We understand why ammonia can be useful to life,” Clements said. “We don’t understand how ammonia is produced, just like we don’t understand how phosphine is produced, but if there is ammonia there, it would have a functional purpose that we can understand.”

However, Greaves warned, even the presence of phosphine and ammonia would not be evidence of microbial life on Venus, because so much information about the state of the planet is lacking. “There are many other processes that could occur, and we simply don’t have any ground truth to say whether this process is possible or not,” she said, referring to hard evidence that can only come from direct observations from the inside. the planet’s atmosphere.

One way to make such observations would be to persuade the European Space Agency to turn on some instruments on board the spacecraft. Explorer of Jupiter’s icy moons —– a probe on its way to the Jupiter system —– when it passes Venus next year. But even better data would come from DA VINCIan orbiter and atmospheric probe that NASA plans to launch to Venus in early 2030.

Cautious optimism

From a scientific perspective, the new data on phosphine and ammonia are intriguing but warrant cautious optimism, said Javier Martin-Torres, professor of planetary sciences at the University of Aberdeen in the United Kingdom. He led a study Published in 2021 that challenged the phosphine discoveries and postulated that life is not possible in the clouds of Venus.

“Our paper emphasized the harsh and seemingly inhospitable conditions of Venus’ atmosphere,” Martín-Torres said in an email. “The discovery of ammonia, which could neutralize sulfuric acid clouds, and phosphine, a potential biosignature, challenges our understanding and suggests that more complex chemical processes may be at play. It is crucial that we address these findings with careful and thorough scientific investigation.”

The discoveries open new avenues for research, he added, but it is essential to treat them with a good dose of skepticism. While the detection of phosphine and ammonia in the clouds of Venus is exciting, it is just the beginning of a longer journey to unlock the mysteries of that planet’s atmosphere, he said.

Scientists’ current understanding of Venus’ atmospheric chemistry cannot explain the presence of phosphine, said Dr. Kate Pattle, professor in the department of physics and astronomy at University College London. “It is important to note that the team behind the phosphine measurements does not claim to have found life on Venus,” Pattle said in an email. “If phosphine is indeed present on Venus, it could indicate life, or it could indicate that there is Venusian atmospheric chemistry that we don’t yet understand.”

The ammonia discovery would be exciting if confirmed, Pattle added, because ammonia and sulfuric acid shouldn’t be able to coexist without some process — whether volcanic, biological or something not yet considered — driving the production of ammonia itself.

She emphasized that both results are only preliminary and would require independent confirmation, but they make upcoming missions to Venus, such as the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer and DAVINCI, intriguing, she concluded.

“These missions may provide answers to questions raised by recent observations,” Pattle said, “and will certainly give us fascinating new insights into our nearest neighbor’s atmosphere and its ability to support life.”

For more news and newsletters from CNN, create an account at CNN.com