Documents submitted to the Infected Blood Inquiry reveal that the UK blood service received donations from British prisons until the late 1980s, despite warnings to end the practice.

It is a testament to how unsafe, by current standards, the UK blood supply was until the early 1990s, when tests were carried out to detect potentially fatal viruses such as Hepatitis C It is HIV became available.

Much of the inquiry focused on hemophiliacs, the group most harmed in the infection scandal over imported U.S. blood products made from contaminated blood from paying donors, including those in prison.

But the vast majority of people infected with hepatitis C in the UK acquired the infection through blood transfusions on the NHS for routine surgery, cancer treatment or after giving birth.

The blood given to this silent majority in the infected blood scandal came almost exclusively from donors in Britain.

“I felt so guilty that I passed on it,” says Daphne Whitehorn.

See more information:

Compensation for infected blood ‘will be extended’ to bereaved children

Victims and families of victims press Westminster for compensation

More about infected blood investigation

She contracted hepatitis C from a blood transfusion she received during a kidney transplant in 1971.

“But I didn’t know I could convey it because I was never told anything about it,” she says.

Daphne Whitehorn

Her daughter Janice tested positive for the virus in 2019, likely infected at birth. Neither of them knew they had the infection for decades.

Symptoms may be mild at first, many people clear the virus naturally, and treatments introduced in the last decade can cure the infection for most people without serious side effects.

But chronic infection can cause serious liver damage, liver failure and liver cancer.

The Whitehorns and thousands of other victims of the scandal are turning to the Infected Blood Inquiry for answers.

Chief among them is why so many people have become infected with hepatitis C.

There are no precise numbers, many of the records of donors, recipients and procedures have been lost or destroyed.

But the survey’s statistical experts estimate that around 27,000 people may have been infected with hepatitis C through transfusions. Most later died from other causes, but they estimate that around 1,600 have died so far from causes directly related to hepatitis C infection.

The inquest heard how more could have been done to keep viruses such as hepatitis out of the blood supply.

Janice Whitehorn tested positive for the virus in 2019

Documents show how calls to end the practice of receiving donations from the prison population took a long time to be answered.

The inquiry revealed evidence that in 1973 hepatitis virus rates were five times higher in prisoners than in the general population.

While this has led many regional blood services to stop receiving donations from prisons, others have continued. The last prison donation occurred in 1987.

But the inquiry is also expected to consider much wider failures.

For example, when HIV and then hepatitis C tests became available, the blood service was slow to adopt their use. This is also why stocks of frozen, infected blood collected before the introduction of hepatitis C testing were not retrospectively tested before being administered to patients in the early 1990s.

Furthermore, victims of the scandal want to know why it took four years for the Department of Health to approve a “lookback” exercise to identify those who may have been infected due to a blood transfusion. This is also why this exercise left so many people still unaware that they were infected.

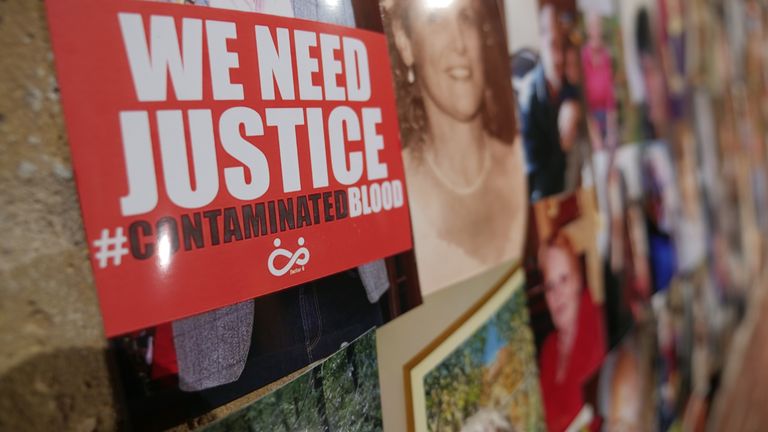

A wall of photos of the victims of the scandal

“We are very sorry for the roles we have played in the past,” said Dr Gail Miflin, chief medical officer of the NHS Blood and Transplant Service.

“Hearing the stories of infected and affected people, they are terrible stories.

“My job as chief medical officer is to ensure that the blood supply today is safe and that people who need a transfusion today receive blood from one of the safest blood services in the world.”

Keep up with the latest news from the UK and around the world by following Sky News

And a lot has changed.

Donors today are screened for lifestyle factors and travel history that may have put them at risk for blood-borne infections.

Each donation is also tested for a range of infections, including HIV and hepatitis C, and a sample from each donation is archived for three years in case retesting is necessary.

The Infected Blood Inquiry is expected to publish its final report on May 20.

If you think you may be at risk of hepatitis C infection, free testing is available in England: in Wales: In Scotland you will need to speak to your GP.

This story originally appeared on News.sky.com read the full story