William Freeman was destitute, disabled, with almost no friends and no prospects for the future, all before he turned 21.

He had just served five years in Auburn State Prison for stealing a horse; He swore he didn’t do it. The incessant prison work brought him debilitating injuries but not even nominal compensation. All he got when he got out of prison in September 1845 was two dollars, ideally to take a stagecoach or train out of town.

Freeman had few advantages, but he was determined.

“I worked five years for nothing and they have to pay,” he repeated over and over again. What at the time may have sounded like empty murmurs soon turned out to be the heart of a horrific quadruple murder and the subject of an investigation. new book, “Freeman’s Challenge”.

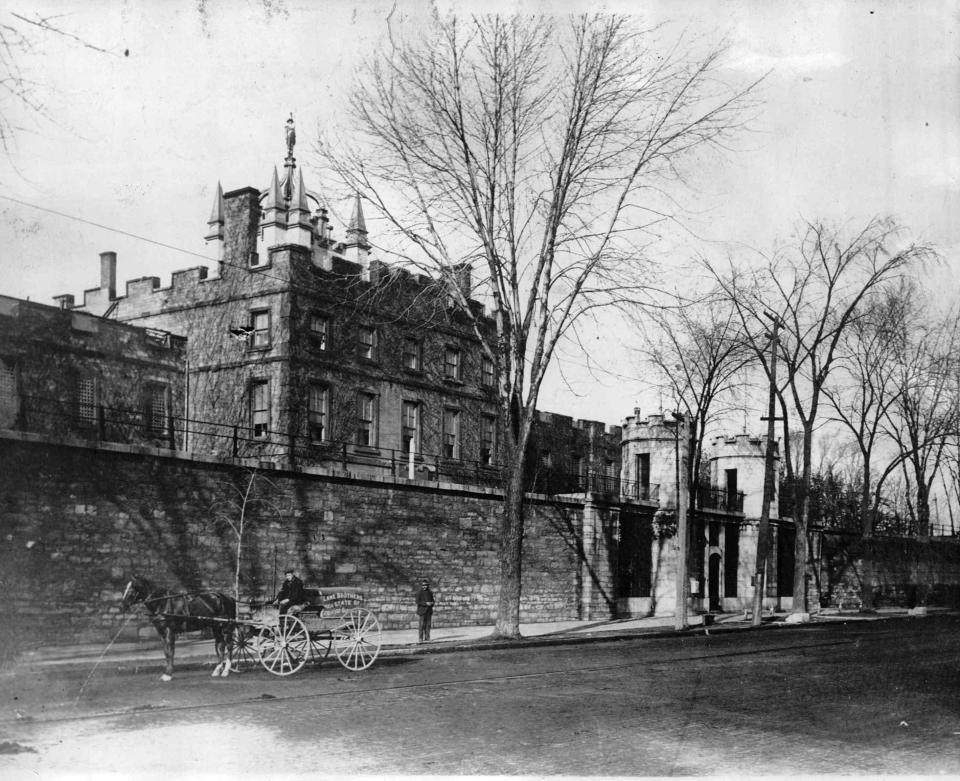

Author Robin Bernstein, a historian at Harvard University, uses Freeman’s case to interrogate the economic and racial underpinnings of the North’s ancient prison system. Auburn State Prison, founded in 1817 and operating continuously to the present, was one of the most influential prisons in the United States.

At issue was the very purpose of incarceration. Advocates elsewhere have posited rehabilitation or punishment. Auburn found a third way: profit.

“Unlike their counterparts who built prisons in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and other nearby states, Auburn’s leaders had no discernible interest in reform,” Bernstein writes. “They saw a prison as a vehicle to absorb state funds, build banks, stimulate commerce, manufacture goods, and develop land and waterways. In short, they reinvented prison as an infrastructure for capitalism.”

The role of unpaid convict labor

When 15-year-old Freeman was incarcerated in 1840, the system was working exactly as designed. The city of Auburn had grown and almost the entire local economy depended on the prison in one way or another.

The unpaid labor of convicts was given prominent consideration. Freeman, whose grandfather was enslaved by the city’s founder, fiercely rebelled against prison rules that prohibited speaking, looking people in the eye, or otherwise interfering in the industrial apparatus. He was repeatedly beaten while incarcerated, including one particularly brutal incident that left him deaf and, perhaps, mentally disabled for the brief remainder of his life.

More: Rochester Man Wrote First Black Auburn Prison Memoir

Repeatedly after his release, Freeman demanded restitution for his prison work, to no avail. His constant refrain – “they have to pay” – became distinctly threatening.

About six months after his release from prison, Freeman walked three miles south of Auburn, eventually arriving at a house owned by a local white family for whom he had briefly worked. He knocked and was allowed to enter, then stabbed five inhabitants, killing four.

Among them were a pregnant woman and a 2-year-old boy.

The crime shocked the region. When he was captured the next morning, Freeman gave a consistent but apparently insufficient explanation: “(He) said the state owed him five years of work and they had to pay him, or someone had to pay him.”

In this sentiment, Bernstein finds an eloquent, if unexpected, indictment of the brutal conditions at Auburn State Prison, as well as the economic basis of the institution and the city itself.

“Freeman saw what anyone could see if they wanted to look: the state and the prison operated through each other, both politically and economically,” she writes. “The resulting violence could not be confined to prison, no matter how thick the walls were.”

This was not the popular view at the time. White journalists, prosecutors, clergy, and the general public rejected Freeman’s explanation and proposed others. The crime was proof of the inherent savagery of black people, they said — but not of insanity, a defense that could have kept Freeman from the gallows.

William Seward enters the story

Freeman was defended by Auburn’s most prominent citizen, former New York governor and later Secretary of State William Seward. He admitted the inherent deficiencies of blacks, but placed the blame for the crimes on white society for failing to lift Freeman and the rest of Auburn’s small black population from their natural degraded state.

“The prosecution and defense agreed, then, that blacks needed assistance and supervision from whites—without which they would commit crimes,” Bernstein writes. “In both narratives, the Freeman murders proved that white people needed to control black lives.”

One jury determined that Freeman was reasonable enough to face murder charges and another quickly convicted him. He avoided execution only by dying in prison in August 1847, aged 22.

Freeman’s criticism was largely ignored during his lifetime, but was picked up by Frederick Douglass, who called his demand for compensation a “just demand”.

Bernstein agrees and frames the 180-year-old story within a modern call for prison abolition.

“Prison as we know it was built, challenged, defended, adjusted, and re-consolidated by individuals who worked together,” she writes. “By understanding their actions, we can imagine alternatives.”

—Justin Murphy is a veteran Democrat and Chronicle reporter and author of “Your children are in great danger: school segregation in Rochester, New York.” Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: ‘They have to pay’: book finds criticism of prison in quadruple murder