On a Tuesday in March, Annabelle Rogers finished choir class at Hopkinton High School. She then headed to the school gym, which that day also served as the official voting location for the municipal elections.

Rogers recently turned 18, making her eligible to vote. But she doesn’t have a driver’s license and didn’t bring any other identification to school that day. Still, she was allowed to register and vote.

“I got a sticker, which was really cool,” Rogers said.

Everyone else who voted that day in Hopkinton – and in elections across the state – was entitled to a secret ballot, a cornerstone of American democracy that ensures that election participants are free from intimidation or coercion.

But because of a relatively new and little-used state law, Rogers received a different vote. Hers was numbered and traceable. If she did not return proof of eligibility within seven days, her vote would not count – and the candidates she chose on her ballot that day could become publicly available information, without her knowledge or consent.

“It’s actually a little scary,” she said. “This is a little stressful.”

Some people warned about this same consequence – the disclosure of voters’ individual electoral choices – when the law was being debated in the State House.

The Republican-backed law signed by Governor Chris Sununu in 2022 launched the use of provisional votes for first-time voters who do not have proper identification when registering at the polls.

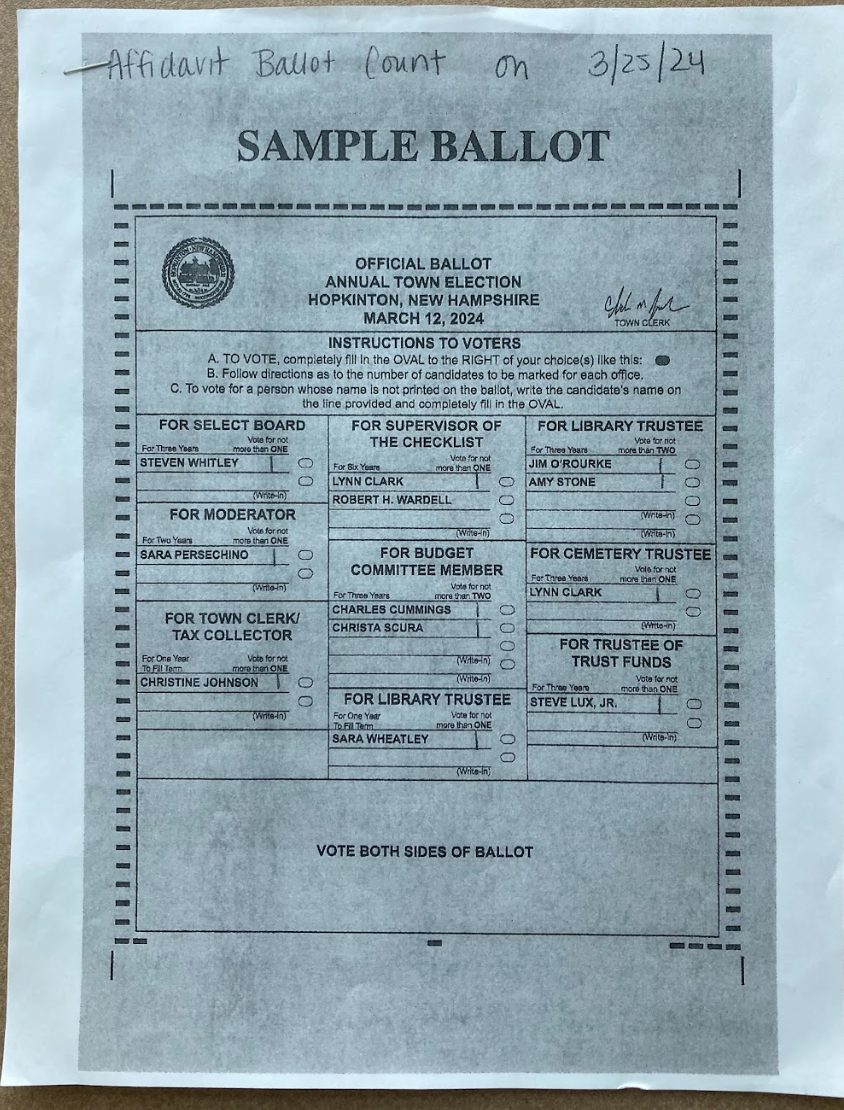

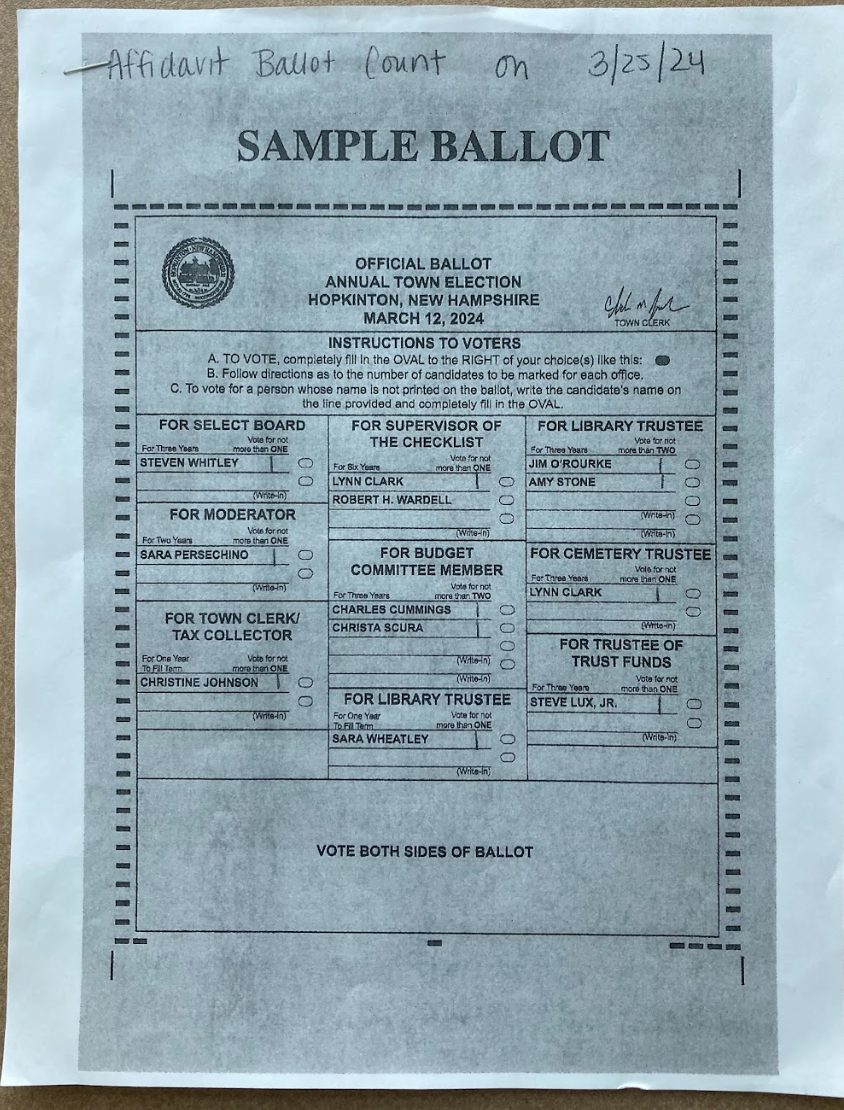

Under the law, voters like Rogers can cast something called an “affidavit ballot”; they then receive a prepaid envelope and instructions on how to send it as proof of their identity.

When Rogers failed to return the paperwork in time, the New Hampshire Secretary of State’s office instructed election officials in Hopkinton to delete her votes from the final tallies — as if she had never appeared at the polls.

Although the Secretary of State’s office does not release the names of voters who use declaration ballots, it does publicly disclose the towns and cities where they are used. A review of voting rolls in Hopkinton revealed that only one person registered at the polls without identification on Town Meeting Day in March: Annabelle Rogers. Revised vote totals released more than a week after the election provided the final link in the chain: who Rogers voted for, before her votes were erased.

“I understand why they had to delete the vote,” she said. “But they should probably do it in a way that doesn’t make it public.”

New Hampshire Secretary of State David Scanlan previously defended the law, saying it implemented “reasonable controls” for those seeking to vote without identification, but declined an interview request for this story. He also did not answer written questions, including whether he believes voters with an affidavit have the same right to a secret ballot as all other voters.

Rogers said she was told at the polls that her vote would be void if she didn’t submit her paperwork on time. But she didn’t know until NHPR contacted her that her voting preferences could become public.

“It’s a bit detective, but you can see how someone could easily do this if they really wanted to,” she said.

A fear for voters, he realized

Republicans passed the sworn voting law citing the need to increase public confidence in the electoral process. Previously, anyone registering for the first time in New Hampshire without showing identification could sign an affidavit swearing to their eligibility to vote. Although they could later be investigated for possible electoral fraud, their ballots were not traceable, which meant that their votes could not be deleted from the final counts if fraud was detected.

Since the law took effect in 2023, five declaration ballots have been cast in New Hampshire: one each in Hopkinton, Hooksett and Derry, and two in Manchester. On just two occasions – in March of this year in Hopkinton, and last November in Manchester — the voter did not mail in a copy of the required identification, resulting in the vote being deleted.

NHPR was able to confirm the identity of the Manchester voter whose vote was cancelled, but they declined to be interviewed and requested anonymity, so we are not naming them in this story. Like Rogers, they recently turned 18.

In Hopkinton, local election officials said they instructed Rogers to return the paperwork, explaining that otherwise his votes would be erased. Rogers confirmed that he understood this step of the process. However, she said her grandparents, who she lives with, were uncomfortable with her mailing confidential documents and instead told her she should register with city hall at another time.

“They said, ‘We don’t know if we like this,’” Rogers said. “They can be very cautious about this kind of thing.”

She decided to forego submitting the paperwork, in part because the stakes in the city’s elections this spring seemed relatively minor: The only contested race was for checklist supervisor. Positions such as library and cemetery administrator were unopposed.

“That wasn’t a big deal because it was a pretty loose election,” Rogers said. “There wasn’t much voting.”

But local election officials and voting rights advocates were not so quick to ignore what happened to Rogers under the new law.

“We should all agree that every voter in New Hampshire should have the right to a secret ballot,” said Hopkinton town moderator Sara Persechino. “I think this is a true principle of our democracy in our country.”

Liz Tentarelli, president of the nonpartisan League of Women Voters of New Hampshire, said her group warned that this same scenario — that other people could find out who someone voted for — could be a possibility when the law was up for debate.

“These are your neighbors. These are people from your own community who are now invading a private ritual,” she said, adding, “I think it’s just appalling.”

Almost immediately after Sununu signed the new law, the ACLU of New Hampshire and another coalition of progressive voting rights groups challenged in court — citing concerns about its effects on voter privacy. These cases were fired for procedural reasons, in part because those suing have been unable to name anyone who was directly affected, and are now before the state Supreme Court on appeal.

Henry Klementowicz, an attorney for the ACLU, said the fact that some voters’ preferences can be made public through the use of ballots justifies concern that the system “intrudes on an important part of American democracy — the right to vote.” secret”.

“We opposed SB 418 in the legislature for exactly this reason,” he added.

Another lawsuit filed by the Democratic National Committee is still ongoing, but a high court judge denied a request for a preliminary injunction, meaning the law remains in effect and in effect.

The New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office, which defends the constitutionality of the law, has argued in court filings that the declaration voting process creates a “low risk of erroneously disenfranchising a person.”

Lawyers for the state told the court that “clearly sufficient procedural safeguards exist to ensure that a qualified voter who wishes to register to vote and cast a ballot will be able to vote in an election.”

Cleared of irregularities, but vote deleted

In the State House this year, Republicans are supporting a New proposal this would further restrict access to voting for those without proof of eligibility at the polls.

Under current law, voters who do not have the correct documents on election day can sign declarations certifying that they are U.S. citizens and live where they are trying to vote. Under the new bill, which has passed the New Hampshire House and awaits Senate action, voters would be required to present a passport, birth certificate or naturalization documents to register — no exceptions.

If the bill becomes law, it would also effectively end the new affidavit voting process.

However, all voters who do not have identification at the polls and do not provide proof of eligibility within seven days are automatically referred to the New Hampshire Attorney General’s office for investigation into whether they violated any election laws.

According to a memo provided by that office to NHPR, a state investigator was unable to make contact with the Manchester voter who used an affidavit ballot in the 2023 municipal election last fall. But they confirmed his age and identity by obtaining records from the Manchester School District.

“This office concludes that there is no evidence to suggest that [name redacted] was not eligible to vote at the time of the November 7, 2023 elections in the City of Manchester,” the memo says. “Therefore, this matter is closed.”

That investigation may have ended, but that voter, who was deemed qualified to vote, still saw their vote permanently erased from the election results. In a quirk of the voter registration process, voters in Manchester and Rogers in Hopkinton are now legally registered to vote in future elections.

Rogers said the increased tension over American elections in recent years makes the secret ballot even more vital.

“It’s really important for people to have that privacy because you don’t want people to do extreme things because of politics,” she said.

These articles are being shared by partners at The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

This article originally appeared in the Portsmouth Herald: According to the new NH voting law, the right to a secret ballot is not guaranteed