They were people of the shadows, moving beyond the light of small fires on a winter dawn. There was no indication that I was about to encounter one of the most extraordinary landscapes of my time in South Africa.

In this part of the country, winter is a cold, dry season that burns the savannah. The ground is hard as stone and when the wind blows across the plains, dust covers the invaders and everything they carry.

I could hear digging and, getting closer, I saw a woman cutting the earth. Nearby, other men and women were doing the same thing. They had old gardening tools, machetes, pieces of stone, anything to make holes where they placed pieces of plastic, tin and wood.

I asked the woman what she was doing. “We are hiding our shacks,” she told me.

This was a clandestine camp on the outskirts of Johannesburg in 1994, as South Africa was preparing to vote in its first non-racial elections.

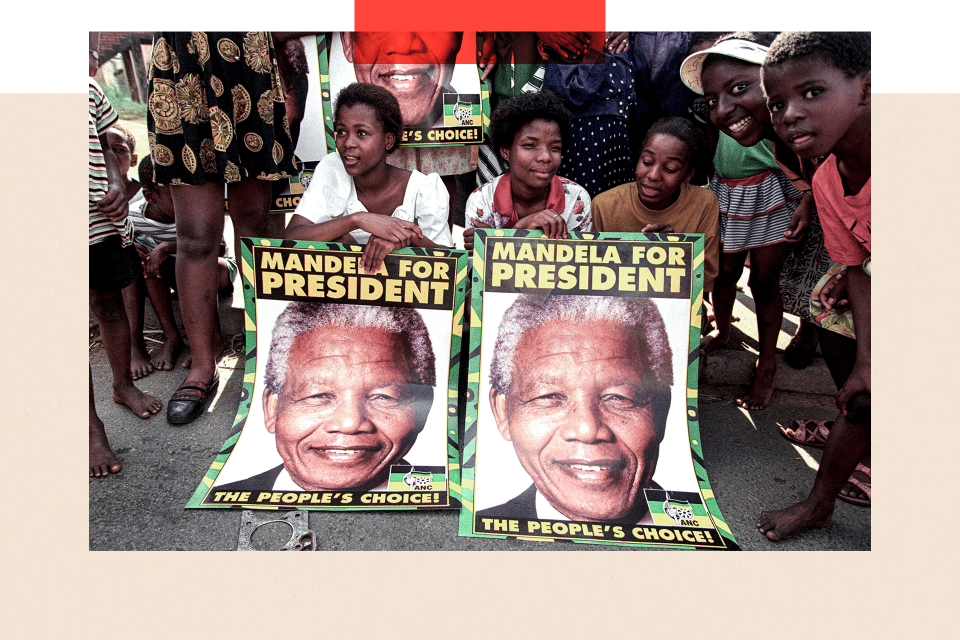

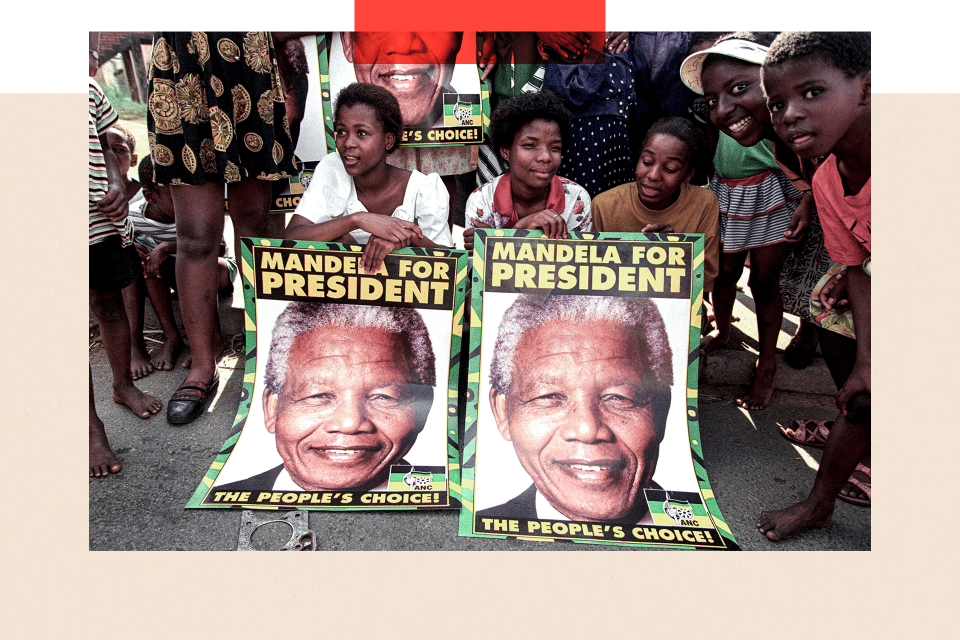

Seeing that vote in a nation brutalized by apartheid was witnessing an inspiring moment in human history. The early voters – mostly elderly – who voted silently pushed history inexorably forward.

Thirty years later, South Africa is a very different country. Democracy resisted. The fear and racist brutality of the past are gone. But there has been widespread disillusionment with the African National Congress (ANC), in power since Nelson Mandela became the country’s first black president.

At that time, the woman hiding her cabin told me her name was Cynthia Mthebe. Her story stayed with me for more than 30 years.

As the sun rose, the squatters’ camp gradually disappeared beneath the earth. An hour earlier, there was a community with dozens of shacks and flimsy tents. Now there were only people, wrapped in blankets, sitting around the fires.

Children dressed in school uniforms headed towards the main road, about a mile away, beyond the fields. No matter the degradation they suffered here, parents fought to give their children an education.

Cynthia had seven children and took care of them alone. Her husband abandoned the family several years earlier and has not been heard from since.

Every day she and the other squatters buried their houses so that they would not be demolished by the government. And every night Cynthia came back, dug up her house and slept there with the children. They were attacked with tear gas and shot with rubber bullets, but still returned. There was nowhere else to go.

“I want to live in a beautiful house with my children because I am suffering. I want to be like white people. I’m suffering because I’m black,” she said at the time. Cynthia fed her family by working at a garbage dump, collecting cans that she sold for a pittance. Just enough to sustain life on the margins of existence.

Unfolding the narrative of her life is the story of millions of South Africa’s poorest people. She was born on a white-owned farm in 1946 – two years before Afrikaner nationalists came to power and began implementing the policy of apartheid. .

Racial discrimination was written into law. Every aspect of the lives of non-whites – where they could live, what jobs they could hold, who they could marry – was brutally policed by the white government. Torture, disappearances, and daily humiliations haunted black lives.

Under so-called Grand Apartheid, the state would dump millions of black people into arid tribal “homelands” where they would be given nominal independence. In reality, they were abandoned to poverty under the rule of despotic local leaders. Then there were the laws under which people were classified racially. One of the running tests involved sticking a pencil in a person’s hair. If it passed without obstruction, they were classified as white. Otherwise, they would be thrown into the world of apartheid discrimination.

One of Cynthia’s many painful apartheid memories is of her time working as a maid in a white house in Johannesburg. She was offered some leftover food and she began to eat it from a plate belonging to her employers. “The hostess told me I should never do that, eat from the same plate as them. It was like I was a dog,” she told me.

Cynthia Mthebe was one of the tens of millions to whom Nelson Mandela promised a land of equality and justice upon his release from prison in 1990. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech three years later, the ANC leader spoke of the South -Africans become “the children of Paradise”.

As South Africa entered the final days of its 2024 election campaign, I headed to the rural heart of the country’s northwest to see Cynthia, far from the Ivory Park squatter camp where we met.

Mandela has been dead for more than a decade and his party, Africa’s oldest liberation movement, is losing popularity. There is widespread disillusionment about official corruption – estimated to have cost billions of pounds – and poor governance. South Africa remains the most unequal society on the planet, with the average white family likely to be 20 times wealthier than their black counterparts, according to one study. Successive polls have shown that the ANC is at risk of losing the overall majority it has held since the first democratic elections in 1994.

The last leg of the trip to Cynthia takes me along a dirt trail, past meandering cattle, a man weeding his vegetable garden, and groups of women and children returning from church. You can hear the tinkling of cowbells and kwaito (a distinctly South African version of House music) playing on a radio in one of the small brick huts that dot the landscape in Klipgat, the town where Cynthia moved seven years ago.

I recognize the blue house with the lemon tree in the garden. I’ve been here before. In 30 years I have never lost contact with Cynthia and her family. I see the elderly lady approaching through the yard. She leans on the arm of her granddaughter Thandi, a member of Cynthia’s family with nine children, 13 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

Cynthia reaches out her hands to hold mine and then wraps her arms around me. “Fergal, it’s you,” she says. Cynthia is now blind. The woman whose sharp eyes once watched over her family in the squalor of illegal camps now lives in a world of darkness and sounds.

She is also diabetic. The years of working in landfills and living in shacks took a heavy toll. However, her home is a place of safety and peace. The facilities at the local clinic are better than those available in the city. Cynthia also receives a monthly social assistance allowance of 2,000 rand (about US$108; £85).

But the house was built by the children, with the money they patiently saved by doing whatever work they could find. His oldest daughter, Doris, found work at a white-owned store. Eldest son Phillip works in the markets in Pretoria, about an hour away. Grandchildren also help. When I originally filmed with Cynthia in the 1990s, there was an outpouring of support from the BBC audience, who sent money to help the family.

The Mthebes stayed together as a family through their own efforts, and not because of what was given to them by the state or anyone else. “Even now things are not better,” says Cynthia. “I’m trying… (to survive) in every way.

“But I don’t have the power because we don’t have food if I don’t have money, because the subsidy is very small.” Nowadays, it is Doris who provides most of what her mother needs to live, while also helping her own son and daughter.

Cynthia is angry with the government. “There are no jobs… people are suffering. But they [the ANC] say vote for me, vote for me always. I’m not going out to vote. For what? Because it doesn’t matter. The government does nothing for us.”

She points to the absence of running water in her home, the frequent power cuts in the area due to the depletion of the country’s energy grid, many of which are caused by corruption and a lack of investment.

The ANC admits it made serious mistakes, but points to the legacy of inequality from more than three centuries of white rule, something that could not be overcome in 30 years. The party claims to have built millions of homes, provided essential services to the poor and provided more clinics and hospitals. The official estimate is that 1.4 million are still waiting for homes – many believe this number is a considerable underestimate. The fact is that much more could have been done if so much money and energy had not been wasted by corruption and factional struggles within the ruling party.

Cynthia’s views on South Africa and the ANC – she proudly supported Mandela in 1994 – are heavily influenced by her family’s experience. His middle son, Amos, was shot by criminals and is now lame, struggling to find work in a country with an unemployment rate of over 30%. Crime in South Africa harms black South Africans the most.

Around 25,000 people were murdered last year, one of the highest homicide rates in the world. Cynthia’s second daughter, Joyce, was abandoned by her husband and is also unemployed. Another son, Jimmy, died from alcohol abuse in a township near Johannesburg.

More from InDepth

The family asked me to show them the original films I made in the 1990s. We sat in the warmth of the tin-roofed room as the past unfolded on my laptop screen. Cynthia in the tent at night. Cynthia working at the garbage dump. The younger children helping her. Jimmy, already lost to alcohol, looking away.

Watching her own story, tears streamed down the faces of Doris, Amos and Thandi. A great-granddaughter put her hand to her mouth in shock when she saw Cynthia searching the landfill.

Then Doris spoke. “I want to thank you, mom. I am who I am because of you. I love you.” Amos wiped his eyes and, struggling to speak, said, “What can I say about a mother like that. I’m so proud of her.”

Cynthia could only hear the sounds of that past world on the computer and now she heard the words of her children. She was smiling. An old, blind woman surrounded by love. A courageous survivor of her nation’s struggles.

BBC in depth is the new website and app for the best analysis and experience from our top journalists. Under a distinct new brand, we will bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and in-depth reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be featuring thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25516719/Alphabet_Mineral_Rover.jpg?w=300&resize=300,300&ssl=1)