Syeda X, a poor migrant woman living in slums near India’s capital Delhi, has struggled to get more than 50 jobs in 30 years.

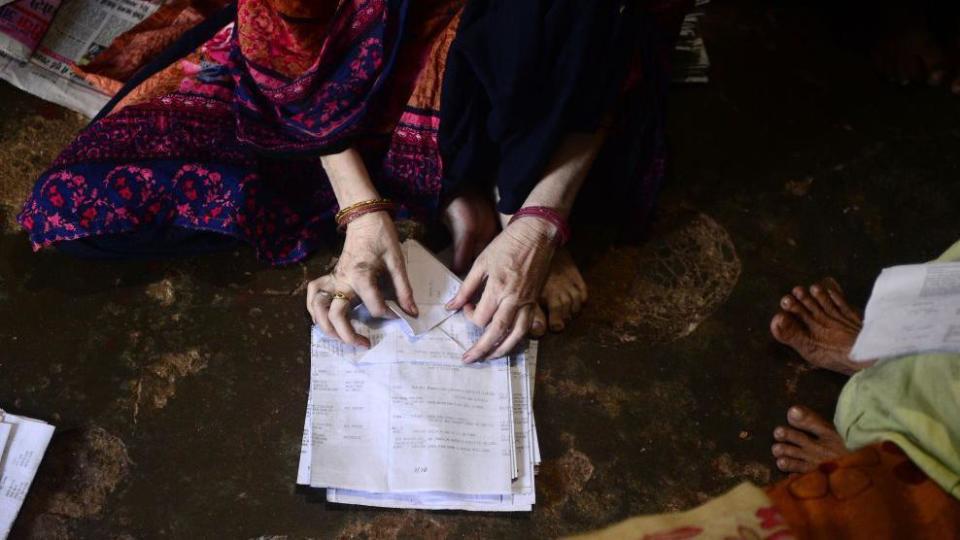

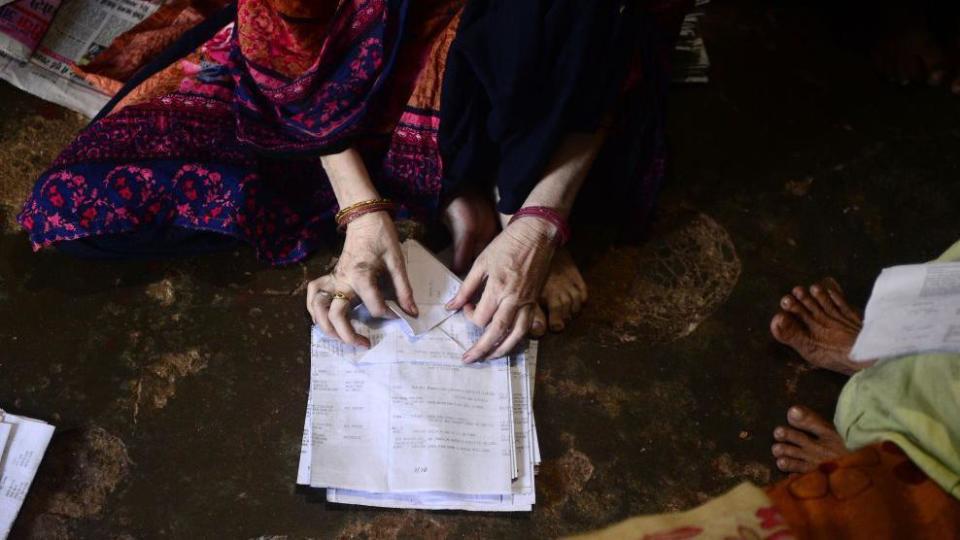

She cut threads from jeans, cooked snacks, shelled almonds and made tea strainers, door handles, picture frames and toy guns. She also sewed school backpacks and did beadwork and jewelry. Despite her hard work, she earned meager wages, such as 25 rupees (30 cents; 23 cents) for assembling 1,000 toy guns.

The protagonist of a new book, The Many Lives of Syeda X, by journalist Neha Dixit, Syeda moved to Delhi with her family in the mid-1990s, following religious riots in the neighboring state of Uttar Pradesh. Reported over 10 years with more than 900 interviews, the book highlights, in part, the precarious life of an Indian domestic worker.

Dixit’s book highlights the invisible lives of India’s neglected home-based workers. After being officially recognized as distinct category of workers only in 2007, India defined a home worker is someone who produces goods or services for an employer in their own home or chosen premises, regardless of whether the employer provides equipment or materials.

More than 80% of working women in India are employed in the informal economy, with home-based work being the largest sector after agriculture. However, no legislation or policy supports these women.

Wiego, an organization that supports women in informal employment, estimated that between 2017 and 2018, women represented around 17 million of the 41 million home-based workers in India. These women represented approximately 9% of total employment. Their numbers in the city grew faster than in interior India. “The center of gravity for home-based workers appears to be shifting to urban areas,” says Indrani Mazumdar, a historian who has worked extensively on the subject.

Deprived of social security or any protection, these women are in a constant battle against poverty, precariousness and rebellious spouses. Often being the family’s main breadwinner, they struggle to earn enough to educate their children to escape poverty. These women also face the brunt of climate change, losing livelihoods and suffering losses: the flooding of their homes by the monsoons leads to wastage of the material provided.

In India, around 75% of female manufacturing workers work from home, says economist Sona Mitra. “These women are registered as self-employed and are largely invisible,” she adds.

Ms. Dixit’s harrowing narrative portrays Syeda X and other women who work from home as archetypes of helplessness and exploitation. No one knows who sets the terrible rates for your work. No one provides instructions, training, or tools. These women only depend on each other to learn how to get the job done.

Finding work often also involves keeping up with the news cycle, Dixit writes.

When Kalpana Chawla became the first woman of Indian origin in space in 1997, the women dressed plastic dolls in hand-sewn white spacesuits. During the 1999 cricket World Cup, they sewed hundreds of cheap footballs. A 2001 viral rumor about a “Monkey Man” attacking people in Delhi has spurred a demand for masks resembling the creature to be sold at traffic intersections. During the elections, they made flags, keychains and caps for political parties. When schools resumed, they packed colored pencils, school bags and bound books.

Many women also have difficulty finding work from home for more than 20 days a month. Dixit writes that only those who don’t negotiate rates or ask too many questions, buy their own tools, deliver on time, never ask for advances or help during crises, and tolerate late payments can find work easily.

The precariousness of domestic workers has increased due to changes in the nature of work, according to Mazumdar. Until the 1990s, the ready-made garment industry outsourced many tasks to domestic workers. This situation changed in the 1990s, as factories began to bring tasks in-house and machines replaced human labor, especially in embroidery. “Home working has become very volatile,” she says.

In 2019, the International Labor Organization, based on household surveys in 118 countries, estimated that there were around 260 million home-based workers worldwide, representing 7.9% of global employment.

Research carried out in Brazil and South Africa shows that it is possible to monitor working conditions and protect the rights of workers in subcontracted work or at home when local governments and unions collaborate effectively.

Such examples in India are few and far between. There is the 52-year-old Self-Employed Women’s Association (Sewa), a membership-based organization that unites poor women who are self-employed in the informal economy. There are home-based worker self-help groups and microfinance to support them. “But these schemes have not really helped them when it comes to employment,” says Mazumdar.

In 2009, women in Delhi who shelled and cleaned almonds from their homes stopped working, demanding better wages and overtime, among other things. (They were paid 50 rupees to clean a 23 kg bag for 12 to 16 hours.) The strike paralyzed the almond processing industry in its peak season.

A to study in the state of Tamil Nadu, by social scientist K Kalpana, illustrated how domestic and neighborhood workers subcontracted to do applause (papadum) in Chennai successfully defended their rights despite government agencies ignoring the unions’ demands.

Syeda X and his friends were no such luck. “If she ever took time off to nurse an illness or care for her children, her job would be lost to another faceless migrant who would fight to take her place,” writes Dixit. Commuting and difficulties were the only constants in her life, moving from job to job and from house to house.

Follow BBC India on YouTube, Instagram, Twitter It is Facebook.